Caught in the act: collision of two galaxy clusters ends almost deadly

Galaxy clusters are the largest building blocks of our Universe and they are still growing - mainly through collisions with other galaxy clusters. In addition to their hundreds or thousands of galaxies, clusters are filled with hot gas, which emits high-energy X-ray radiation that traces the structure of these huge systems perfectly.

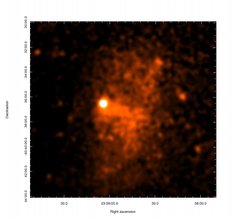

X-ray image of the galaxy cluster RXCJ2359.5-6042 in the 0.5 to 2 keV energy band, which shows signs of the merger of a small, compact system (with a bright core on the left) with the main, extended cluster. The sharp edge of X-ray emission towards the left is probably the effect of a shock, which itself is not clearly visible. The cone shape of this feature is consistent with a low Mach number impact and an infalling speed of the bullet-like compact cluster of typically 1000 kilometres per second. (Note that distances and velocities in space are often much larger than on Earth: here an actual bullet has a velocity of only a few hundred metres per second).

“X-ray observations provide us with the best insight into the structure of galaxy clusters,” says Prof. Hans Böhringer, senior scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE). Hundreds of galaxy clusters have by now been observed with the modern space-based X-ray telescopes XMM-Newton (ESA) and Chandra (NASA). “In about one out of every twenty or thirty systems we find clear evidence that galaxy clusters are currently undergoing a merger.” None of the previous observations, however, has shown such an interesting picture of a merger as the data obtained recently of the galaxy cluster RXCJ2359.5-6042, also known as Abell 4067.

This system was found as part of a systematic search for galaxy clusters (REFLEX II) in the southern sky of the ROSAT all-sky X-ray survey, performed in the 1990s. Recent, more detailed X-ray observations by the MPE astrophysicists Gayoung Chon and Hans Böhringer revealed that RXCJ2359.5-6042, which is at a distance of 1.35 billion light years, shows the merger of a small, compact cluster with a large, less dense system. The new X-ray image of the system is shown in Fig. 1.

The large, more extended and less dense cluster is traced by the shallow X-ray emission, extended mainly in a north-south direction. Embedded in this cluster is a very compact X-ray source with a tail through the cluster.

Optical image of the same cluster as in Fig. 1 (greyscale) by the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS), with the X-ray contours overlaid.

“This can be interpreted as the remnant of a small, dense cluster that has fallen into the main cluster,” points out Dr. Chon. “The bright source is clearly extended and its X-ray spectrum matches that of relatively cool gas at a temperature of less than 20 million degrees (about 1.5 keV), while the gas of the main cluster has a temperature of about 40 million degrees (around 3.5 keV).”

As the small system penetrated the larger cluster, its gas halo has been stripped and stretched into a tail; its outer parts have mixed into the gas of the main cluster. The compact, cool core of the infalling system - the former centre of the small cluster - has survived the collision so far. This interpretation is supported by the optical image of the system (see Fig. 2), which shows a big galaxy at the centre of the compact remnant, as found in the majority of all galaxy clusters.

“We can observe the process of the merger very clearly here because the collision happens very close to the plane of the sky,” explains Dr. Chon. “And we can even predict the probable fate of this merger over the next billion years: The gas in the tail will mix with the gas of the main cluster and the cool core will eventually find its way to the centre of the joint system by gravity to form the central cool core of an even more massive galaxy cluster.”

To gain further insight into how the infalling cluster gets stripped and how the gasses of the two components mix, Dr. Chon and Prof. Böhringer have already been granted seven times deeper observations of this object with the XMM-Newton observatory. A better understanding of the processes in this most transparent system will help to better understand the growth of galaxy clusters in general.