The Milky Way’s inner ring

Using a combination of observed stars and a realistic model of the Milky Way, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics have found a new structure in our home galaxy. Just outside the Galactic bar, they found an inner ring of metal rich stars, which are younger than the stars in the bar. The ages of the ring stars can be used to estimate that the bar must have formed at least 7 billion years ago. The existence of this ring makes it likely that star formation from inflowing gas played an important role at these early epochs.

Understanding the global structure of our own galaxy is complicated by the fact that we are situated close to one of its spiral arms in the disk plane. In many directions, stars are obscured by dense clouds of gas and dust. This is especially true towards the centre of the Milky Way, making the inner Milky Way’s structure particularly elusive. Nevertheless, over the past decade, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) have been able to combine data from various observation campaigns with sophisticated computer simulations to create a state-of-the-art model of the inner Milky Way: a slow bar with a peanut-shaped bulge.

Recent surveys have produced a wealth of new data for the inner Milky Way. APOGEE is a large-scale, stellar spectroscopic survey conducted at near-infrared wavelengths. As opposed to optical light, infrared light can more easily pierce though dust, allowing APOGEE to detect stars situated in the dusty regions of the Milky Way, such as the disk and bulge, and determine not only their element abundances but also their positions, line-of-sight velocities, and approximate ages. In addition, the ambitious Gaia mission is charting about one billion stars, providing positional and proper motion measurements. Together both surveys provide all the necessary observational ingredients to determine orbits of stars in the inner regions of the Milky Way. All that is needed is a realistic Milky Way potential to integrate the stars in. This is obtained from the inner Milky Way model created by MPE scientists.

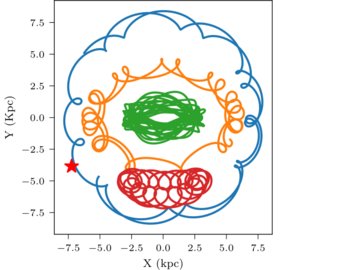

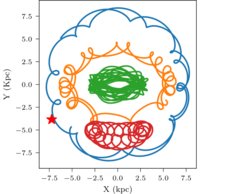

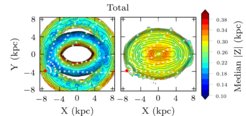

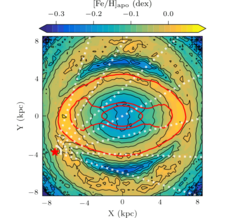

“We integrated more than 30 000 stars from the APOGEE survey with additional data from Gaia in our Milky Way bar-bulge potential to obtain the full orbits of these stars,” explains Shola M. Wylie, PhD student at MPE and lead author of the study. “And with these orbits, we can effectively see behind the galactic bulge as well as other spatial regions not covered by the surveys.” The scientists then used these orbits to build maps of the stellar density, metallicity and age for the inner Milky Way.

“Around the central bar, we found an inner ring structure that is more metal rich than the bar and where the stars have younger ages, around 7 billion years” she continues. While star forming inner rings have been seen in other disk galaxies, it was not clear that our home galaxy contains a stellar inner ring. To separate the stars in the ring and the bar structures, the scientists used the eccentricity of the orbits, i.e. how much the orbit deviates from a circle. They find not only that the stars in the ring are younger and more metal rich than the stars in the bar, but also that these stars are more concentrated towards the Galactic plane.

“Stars in the stellar ring must have continued to form from inflowing gas after the bar was in place”, explains Ortwin Gerhard, lead scientist in the MPE Dynamics Group. Therefore the age of the stars in the inner ring can be used to look back at the formation history of the Milky Way: the scientists estimate that the Galactic bar formed at least 7 billion years ago.

It is still unclear if there is a connection between the newly discovered inner ring and the galaxy’s spiral arms and whether gas is currently funnelled inwards to a star forming, thin inner ring such as seen in other spiral galaxies. Further work is needed to better understand the transition from the ring to the surrounding disk in the Milky Way, requiring augmented models and further data.