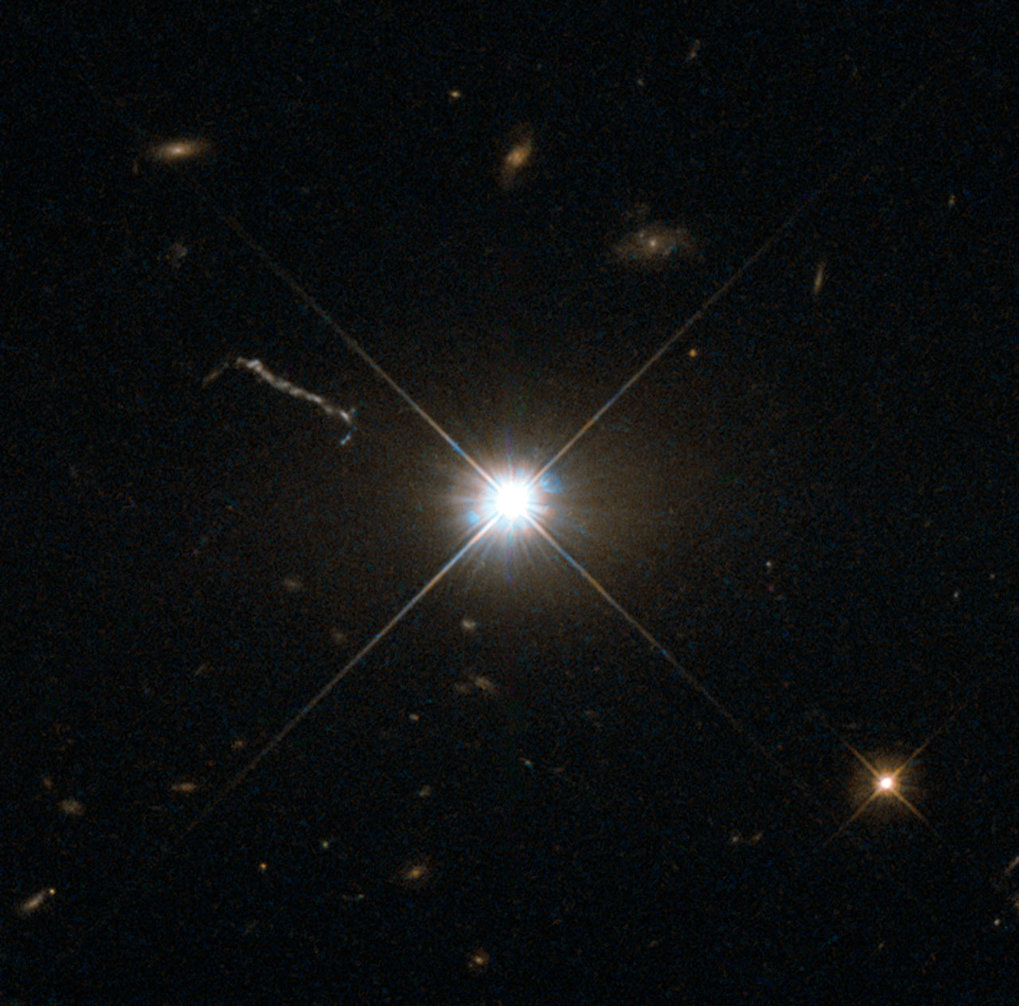

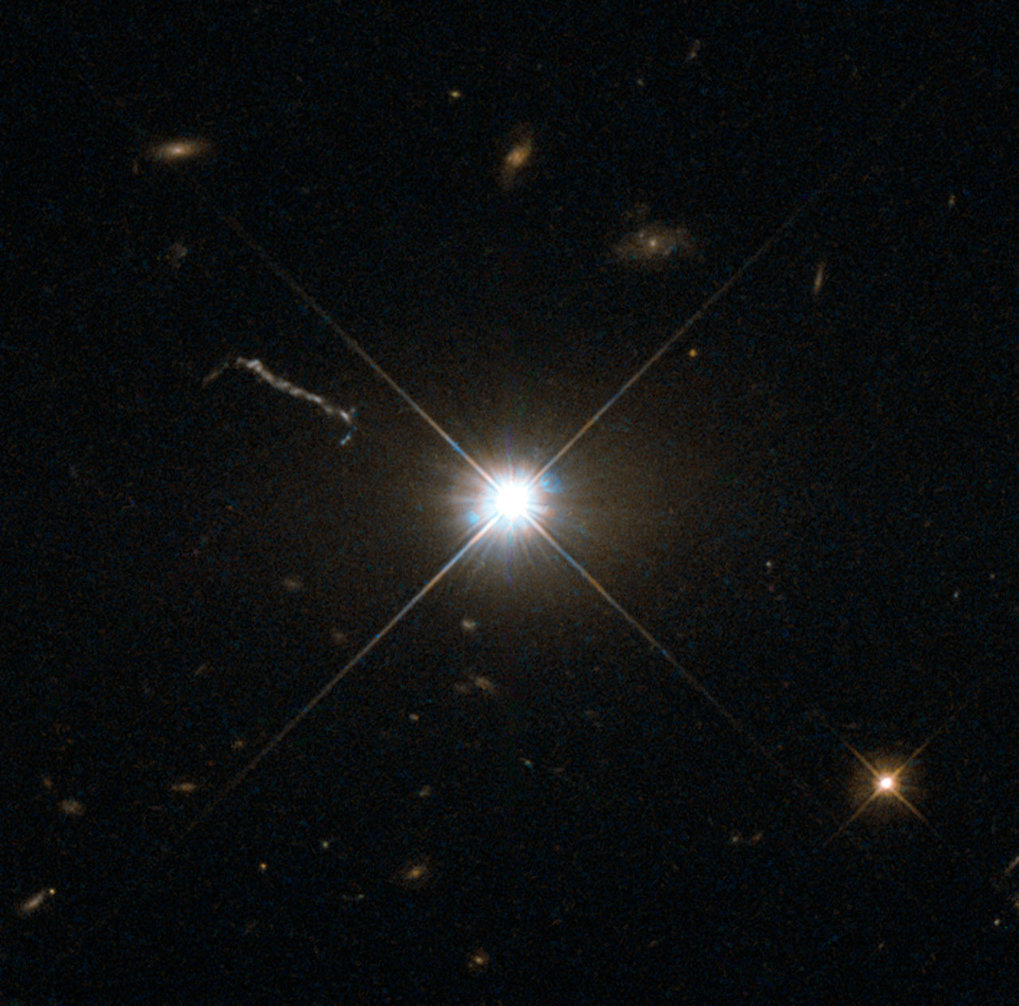

In the whirlpool around a gigantic black hole

Astronomers peer closely into heart of the quasar 3C 273

Detailed observations of the quasar 3C 273 with the GRAVITY instrument reveal the structure of rapidly moving gas around the central super-massive black hole, the first time that the so-called “broad line region” could be resolved. The international team of astronomers was thus able to measure the mass of the black hole with unprecedented precision. This measurement confirms the fundamental assumptions of the most commonly used method to measure the mass of central black holes in distant quasars. Studying these black holes and determining their masses is an essential ingredient to understanding galaxy evolution in general.

More than 50 years ago, the astronomer Maarten Schmidt identified the first “quasi-stellar object” or quasar, named 3C 273, as an extremely bright but distant object. The energy emitted by such a quasar is much greater than in a normal galaxy such as our Milky Way and cannot be produced by regular fusion processes in stars. Instead, astronomers assume that gravitational energy is converted into heat as material is being swallowed by an extremely massive black hole.

An international team of astronomers has now used the GRAVITY instrument to look deep into the heart of the quasar and was able to actually observe the structure of rapidly moving gas around the central black hole. So far, such observations had not been possible due to the small angular size of this inner region, which is about the size of our Solar system but at a distance of some 2.5 billion lightyears. The GRAVITY instrument combines all four ESO VLT telescopes in a technique called interferometry, which allows a huge gain in angular resolution, equivalent to a telescope with 130 metres in diameter. Thus the astronomers can reveal structures at the level of 10 micro-arcseconds, which corresponds to about 0.1 lightyears at the distance of the quasar (or an object the size of a 1-Euro-coin on the Moon).

“GRAVITY allowed us to resolve the so-called ‘broad line region’ for the first time ever, and to observe the motion of gas clouds around the central black hole”, explains Eckhard Sturm, lead author from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE). “Our observations reveal that the gas clouds do whirl around the central black hole.”

The broad atomic emission lines are an observational hallmark of quasars, clearly indicating the extra-galactic origin of the source. So far, the size of the broad line region is measured mainly by a method called “reverberation mapping”. Brightness variations of the quasar’s central engine cause a light echo once the radiation hits clouds further out – the larger the size of the system, the later the echo. In the best cases, the motions of the gas can also be identified, often implying a disk in rotation. This result, derived from timing information, can now be confronted with spatially resolved observations with GRAVITY.

“Our results support the fundamental assumptions of reverberation mapping,” confirms Jason Dexter, co-lead author from MPE. “Information about the motion and size of the region immediately around the black hole are crucial to measure its mass,” he adds. For the first time, the method was now tested experimentally and passed its test with flying colours, confirming previous mass estimates of about 300 million solar masses for the black hole. Thus, GRAVITY provides both a confirmation of the main method used previously to determine black hole masses in quasars and a new and highly accurate, independent method to measure such masses. It thereby promises to provide a benchmark for measuring black hole masses in thousands of other quasars.

Quasars play a fundamental role in the history of the Universe, as their evolution is intricately tied to galaxy growth. While astronomers assume that basically all large galaxies harbour a massive black hole at their centre, so far only the one in our Milky Way has been accessible for detailed studies.

“This is the first time that we can spatially resolve and study the immediate environs of a massive black hole outside our home galaxy, the Milky Way,” emphasizes Reinhard Genzel, head of the infrared research group at MPE. “Black holes are intriguing objects, allowing us to probe physics under extreme conditions – and with GRAVITY we can now probe them both near and far.”

HAE / HOR